Czech Modal Verbs Without Tears

Modal verbs. We all need them to express our desires, necessities, or obligations. They look so innocent, but when you try to use them in Czech, things may get messy. Don’t worry, we’ll sort this out together. And we’ll do it with pizza, because every grammar explanation is better with pizza. I mean, with pizza on paper, not a real one. Sorry if I disappointed you.

Let’s start with some basic examples (with pizza):

- Musím udělat pizzu. → I have to make a pizza. (obligation)

- Mám udělat pizzu. → I’m supposed to make a pizza. (obligation, but less strong than “musím”)

- Smím udělat pizzu. → I am allowed to make a pizza. (permission, also very formal, probably not something you would say in this context, unless a royal gave you permission to make a pizza)

- Chci udělat pizzu. → I want to make a pizza. (intent/desire)

- Umím udělat pizzu. → I know how to make a pizza. (ability)

- Můžu udělat pizzu. → I can make a pizza. (possibility, permission)

See? Just by changing one tiny verb, you’ve got six different relationships to the same pizza. Obligation, desire, ability, even bureaucracy. Welcome to Czech modal verbs.

1. Muset – to have to, must

If you’re an English speaker, you’ll feel at home here: must → muset. Easy, right?

Let’s see the different forms of muset in the present tense:

já musím

ty musíš

on, ona, to musí

my musíme

vy musíte

oni, ony musí (notice this form is identical to the one for on/ona, which is typical for this verb group)

Here are some example phrases in different tenses:

- Dnes musím dopsat seminárku. → I have to finish my seminar paper today.

- Včera jsem musela dopsat seminárku. → I had to finish my paper yesterday.

- Zítra budu muset dopsat seminárku. → I will have to finish my paper tomorrow.

And then there’s the sneaky one:

Už to nemusíš dělat. → You don’t have to do that anymore.

Notice: nemuset is not “must not” but “don’t have to.” Big difference!

2. Mít (mít povinnost) – to be supposed to, should, shall (in questions)

This one can feel tricky because you already know mít as “to have.” However, when mít is followed by another verb in the infinitive form, it turns into something like “should/supposed to.” This second meaning came from the phrase mít povinnost (to have an obligation), which we can also use, but it can sound very formal. See these two sentences: Mám povinnost to udělat. (I have an obligation to do it), or simply: Mám povinnost to udělat. (I am supposed to do it).

Here is mít in the present tense:

já mám

ty máš

on, ona, to má

my máme

vy máte

oni, ony mají

- Máte být potichu! → You are supposed to be quiet!

- Měli jste být potichu! → You should have been quiet!

- Měli byste být potichu! → You should be quiet!

Fun fact: mít doesn’t really form a future tense in this meaning. So you’ll see things like:

- Mám být potichu? → Shall I be quiet?

- Mám otevřít okno? → Shall I open the window?

We also love to use it in phrases like this: Nemáš kouřit! You shouldn’t smoke! Imagine that a friend of yours—a smoker—starts coughing and you tell them: No vidíš – nemáš kouřit! Já jsem ti to říkal(a). Although in English, we might say shouldn’t, there is no politeness in this phrase; it’s rather scolding. If a doctor carefully suggests to a patient that they shouldn’t smoke, they would certainly say Neměl(a) byste kouřit.

3. Smět – to be allowed, may

This is the formal, bureaucratic cousin of moct. We don’t use the affirmative form as often anymore, but it shows up in official contexts.

já smím

ty smíš

on, ona, to smí

my smíme

vy smíte

oni, ony smí / smějí

- Smíte odejít. → You may leave. (very formal, or may feel archaic)

- Směl jsem odejít dřív. → I was allowed to leave earlier.

In reality, you’ll mostly meet the negative form:

- Nesmíš odejít! → You must not leave!

This one is alive and well in everyday Czech. Parents, teachers, pet owners—they all love nesmět. If you are around dog owners, sooner or later you will hear someone say: NESMÍŠ!! Don’t! You’re not allowed! to their dog.

4. Umět – to know how

This is the verb you need when you want to say that you have a skill. English often just uses “can,” but in Czech, we make a difference.

já umím

ty umíš

on, ona, to umí

my umíme

vy umíte

oni, ony umí / umějí

- Umím hrát na piano. → I know how to play the piano.

- Karel neumí říct “ne.” → Karel can’t / doesn’t know how to say “no.”

Important note about pronunciation: When using the negative form (e.g., neumím), we make a small “break” between the letter e and u. Eu is not a diphthong here! Think of it as two separate syllables: ne-umím, ne-umíš, ne-umí. In fast-paced conversations, Czechs might make it sound like eu is one syllable, but you want to speak properly, don’t you?

Have you ever wondered whether a phrase like Umím česky is correct? If not, I wondered for you (není zač!). The full sentence is Umím mluvit česky (I can speak Czech); however, in everyday language, it’s perfectly natural to leave out the main verb (mluvit, in this case). That way, we often end up saying things like Umíš [vařit] svíčkovou? (Can you cook svíčková?) or Neumím kliky (I don’t know how to do push-ups). The reason we can afford to leave the main verb is that, since we have another element in the phrase (for example, the object), the meaning remains clear.

Compare moct and umět:

- Můžu plavat. → I can swim (right now / I’m able / allowed).

- x Umím plavat. → I know how to swim.

5. Chtít – to want

Straightforward: I want. You can use it with verbs or directly with nouns.

já chci

ty chceš

on, ona, to chce

my chceme

vy chcete

oni, ony chtějí (this form is tricky!)

- Chci (si koupit) nové boty. → I want [to buy] new shoes. (It’s common to leave out the main verb when there is an object.)

- Chtěl bych si koupit nové boty. → I would like to buy new shoes. (polite form)

- Chci ven. → I want [to go] outside.

Here is an example with a conditional form:

Nechtěla bych být na tvém místě. → I wouldn’t want to be in your place.

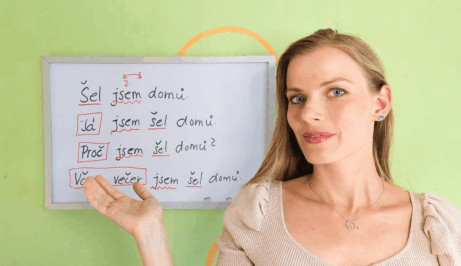

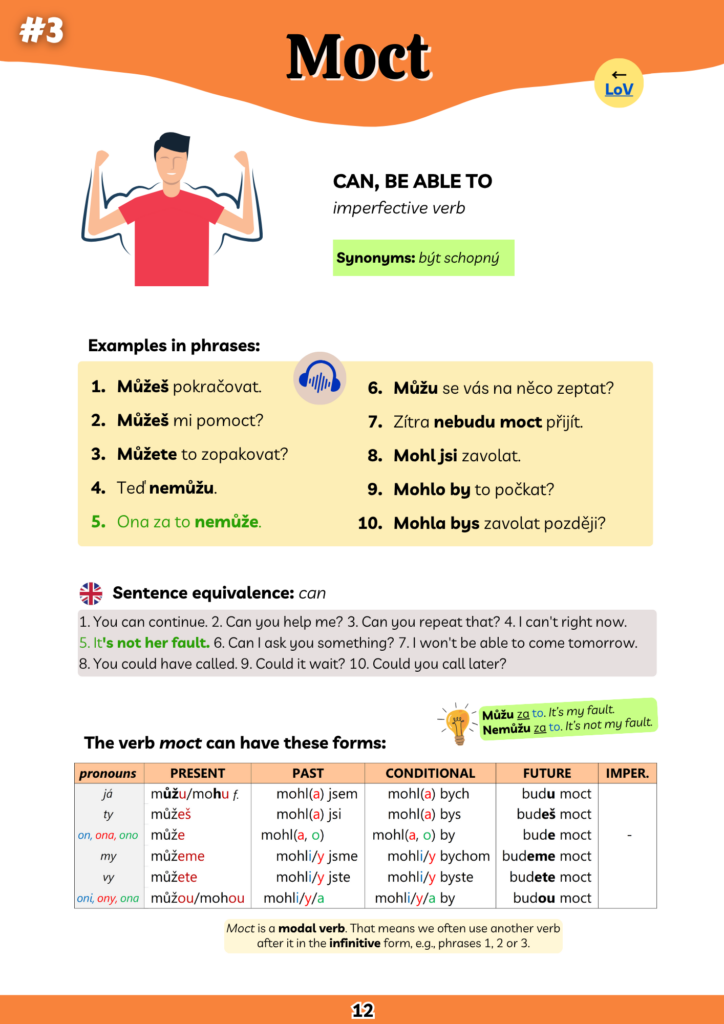

6. Moct – to be able, can

This overlaps with English “can,” both for ability and permission.

já můžu / mohu (formal)

ty můžeš

on, ona, to může

my můžeme

vy můžete

oni, ony můžou / mohou (formal)

- Můžeš mi pomoct? → Can you help me?

- Mohl bys mi pomoct? → Could you help me? (more polite)

- Budeš mi moct pomoct? → Will you be able to help me?

If you want to offer someone help, you can be extremely formal and proper: Jak vám mohu pomoci? How can I help you?, or more casual: Jak vám můžu pomoct?

Pomoci is an archaic infinitive of pomoct. This outdated form is no longer used in spoken Czech, except in a few set phrases.

Remember what I mentioned earlier:

- Můžu plavat. = I am able to swim/allowed now.

- x Umím plavat. = I know how to swim (in general).

You can learn more about these modal verbs in my awesome e-book, The 100 Most Frequent Czech Verbs.

A Dialogue with All the Modals

Here’s how these verbs come alive in a conversation. Scroll down for English translation.

English translation:

Karel: Do you want to drive, Tomáš?

Tomáš: No, I don’t know how to drive stick.

K: What? Why not? Everybody has to know that!

T: How am I supposed to know if I have an automatic?

K: But in driving school you had to drive a manual, right?

T: No, I wanted to get my license just for automatic.

K: That’s nonsense! How could you do driving school only for automatic?

T: You don’t have to anymore. Automatics are modern and actually better!

K: And the result? You can’t help me in an emergency. One day I’ll have to teach you.

T: What emergency? What are you talking about? Don’t take it so seriously, Karel. And what about you, do you know how to drive an automatic?

K: I probably don’t. And I don’t even want to!

T: See?

Final Thoughts

Modal verbs are an important part of languages. Once you get used to their forms and use, you will see how many possibilities you have for making sentences! Just remember:

- Muset = must, have to

- Mít (povinnost) = supposed to, should

- Smět = may, be allowed

- Umět = know how

- Chtít = want

- Moct = can, be able

Write a couple of sentences with these verbs that you can use every day!

Do you enjoy the way I explain grammar? You might want to check out my e-books and video courses. You’re in luck because there is a huge discount (50%) on all my material until December 20th! Click here to visit my Christmas e-shop.