‘Moct’ As You Might Not Know It in Czech!

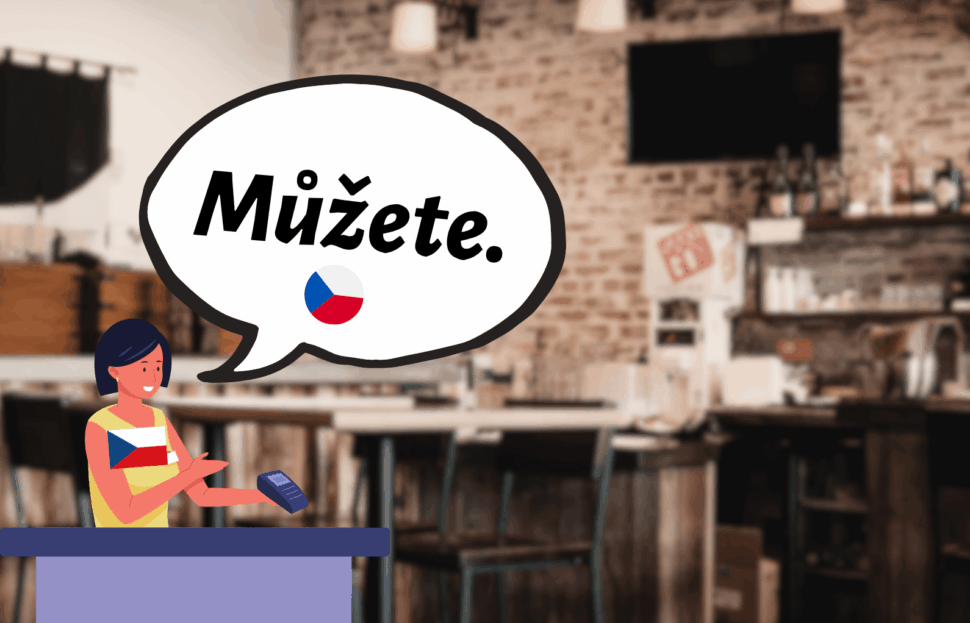

Imagine this: You’re at the café in the Czech Republic, ready to pay by card, and the server points to the terminal and says: “You can.” In English, this might sound a little odd—but in Czech, it makes perfect sense.

In Czech, the server would say: “Můžete.” It simply means: You can (tap now) — the terminal is ready. And that sounds completely natural.

In this post, I want to show you a few everyday situations where Czech uses the verb “moct”, but English would express the same idea differently.

Maybe you’d like to watch this in a video:

Now, let’s take a look at a few scenarios:

1. Playing Catch

Imagine you’re playing catch with a friend. You want to signal you’re ready to catch the ball, so you say:

“Můžeš!” (You can [throw it] now.)

You’re basically telling your friend: “I’m ready.”

Or, if you’re the one throwing, you check if they’re ready:

“Můžu?” (Can I [throw it]?)

It’s short and natural. Sure, you could also say:

“Jsi připravený/á?” (Literally: Are you ready?) or “Jsem připravený.” (I’m ready.)

But these phrases are longer and more formal. “Můžeš?” or “Můžu?” is what you’ll most likely hear.

2. Paying at a Café

Now, back to the café example: When the terminal is ready, the server might say: “Můžete.”

Meaning: You can [tap your card]. The terminal is ready for you. In English, we might say: “It’s ready” or “Go ahead.” But Czech simply uses the verb “moct”.

3. From the Movies

I often notice these differences in translations. The other day, I was watching the new Jurassic World Rebirth (in English, with Czech subtitles). In one scene, Zora and Mr. Krebs are waiting for Dr. Loomis’ decision to go to the island.

In the movie, they ask: “You ready?” And the Czech subtitles say: “Můžeme?” This literally is: Can we? But what they really mean is: Are we (mostly YOU) ready?

So here, we use “moct” to express readiness or permission.

4. In the Office

Let’s say your colleague wants to ask you something, but you’re still writing an email. When you’re ready, you turn to them and say:

“Tak už můžeš.” (Now you can.)

Alternatively, už můžu. (Now I can.)

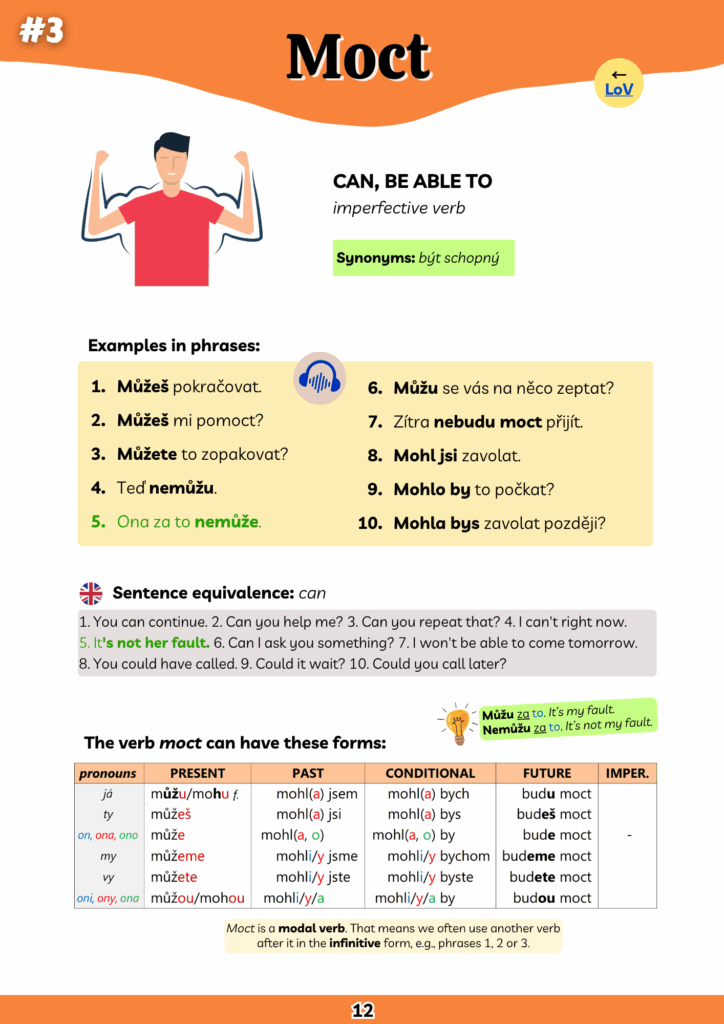

Wondering how we use the verb “moct” in different forms? For this context, we only need the present tense:

já můžu (mohu is also possible but nowadays it’s very formal)

ty můžeš

on, ona může

my můžeme

vy můžete

oni/ony můžou (or the formal mohou)

This is a modal verb, which means it is usually used with another verb in the infinitive form. For instance: Můžete přiložit. (You can tap the card.)

You can learn how to use this verb in various contexts and see what its other common forms are in my e-book, The 100 Most Frequent Czech Verbs. If you purchase it before July 29th, you can get it with a 15% discount – use the code VERBS15.

Wait, don’t go yet! Let’s practice “moct” in these six situations: