Second Position in Czech

Czech word order is relatively free. – Have you heard this before? It is true if you focus on the word relatively. The word order in Czech is indeed quite flexible, but there are many rules that will keep you on your toes. One of those important things to keep in mind is the so-called second position. Let’s see what it is.

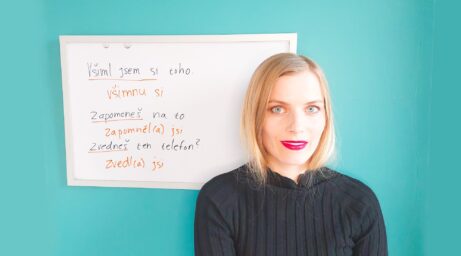

In Czech, certain components of the sentence simply cannot appear at the beginning of the sentence. In other words, they cannot be in the first position. These are short, unstressed words. These components include auxiliary verbs used to form the past tense (jsem, jsi…) and the conditional sentence (bych, bys, by…), the reflexive pronouns se, si, and short forms of pronouns. You will learn all the details soon, but first, let’s take it easy with a couple of simple sentences:

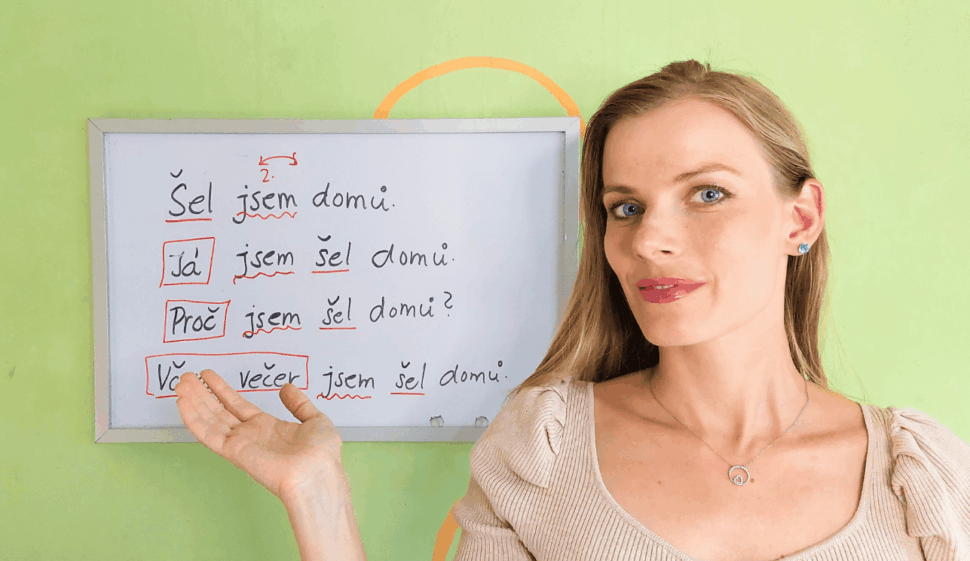

► Šel jsem domů. (I went home.)

First, we used the verb šel, then the auxiliary verb “to be” (jsem).

If we decide to put the pronoun já at the beginning of the sentence for emphasis, the auxiliary verb jsem stays in the same place, but the main verb šel moves after it. In other words, šel and jsem switch positions:

► Já jsem šel domů. ❌ Já šel jsem domů.

The same thing happens when we make a question. Jsem is still in the second position:

► Proč jsem šel domů? (Why did I go home?)

To occupy the second position doesn’t mean it will be the second word of the sentence. There can be a phrase in the first position, such as the phrase včera večer, which cannot be separated:

► Včera večer jsem šel domů. (Yesterday evening, I went home.)

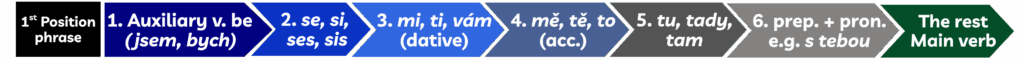

Let’s recap: certain components cannot appear in the first position. They are usually short and unstressed (they don’t carry meaning on their own). These include:

➜ auxiliary verb “to be” (jsem, jsi… for past tense and conditional form bych, bys, by…)

➜ reflexive pronouns se, si

➜ short forms of pronouns (mi, mě, to…)

Let’s look at another example with more components:

► Vrátila jsem se domů. (I returned home.)

In the example above, we have two second-position words, and because they can’t both occupy the same spot, they follow a specific order, a hierarchy. Notice what happens with the second-position words and the main verb when we place a phrase at the beginning of the sentence:

► Už jsem se vrátila domů. (I already returned home.)

► Včera večer jsem se vrátila domů. (Yesterday evening, I returned home.)

► Já bych se vrátila domů. (I would return home.)

Have you noticed how the main verb moved towards the end of the sentence to make room for another phrase? How kind and selfless!

Take a look at the following sentence and pay attention to the words in red (the second-position words) and their order:

► Ptala jsem se tě na to. (I asked you about it.)

Now compare it with these variations:

► Já jsem se tě na to ptala. (I asked you about it.)

► Už jednou jsem se tě na to ptala. (I’ve already asked you about it once.)

The main verb (ptala) did the same thing – it cleared the spot for a new phrase and selflessly moved to the end of the sentence.

The word order will follow the same pattern once there is a word or phrase at the beginning of the sentence:

► Dneska jsem se tě na to ptala. (I asked you about it today.)

► Proč jsem se tě na to ptala? (Why did I ask you about it?)

► Asi jsem se tě na to ptala. (I guess I asked you about it.)

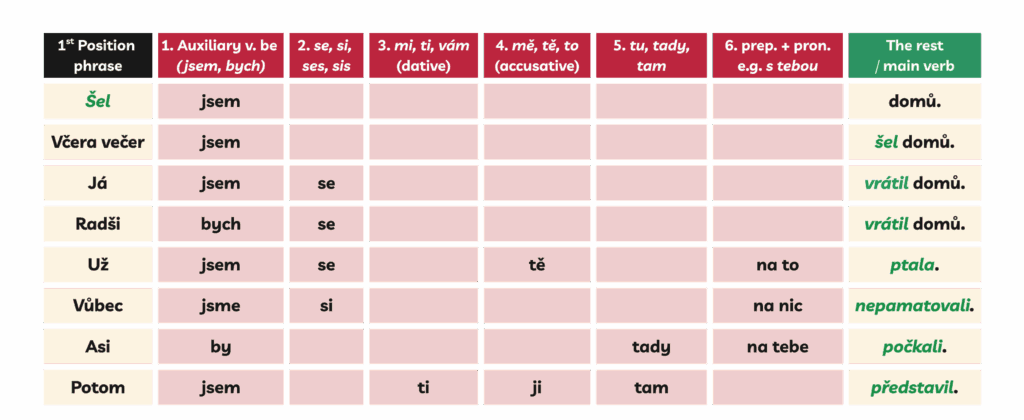

Hierarchy of the second-position words

Here’s a table with several examples. You can see the hierarchy of the second-position words. Kindly note that numbers 5 and 6 can appear at the very beginning of the sentence (as the first-position words). This usually happens in subjective word order, where the speaker wants to emphasize that part of the sentence.

Budu, budeš… Where do they go?

What happens with the auxiliary verb “to be” used to form the future tense (budu, budeš, bude…)? These words do not appear in the second position. They behave quite differently because they form a phrase with the main verb, which appears in the infinitive form (e.g. budu chodit, budeme se těšit…). Look what happens when we start the sentences with budu:

► Budu se na vás těšit! (I’ll be looking forward to seeing you!)

And what happens when we put a different phrase at the beginning?

► Ve čtvrtek se na vás budu těšit! (On Thursday, I’ll be looking forward to seeing you!)

You can see that the verb budu will be either:

a) at the end, with its the second part (the infinitive) also at the end (as it’s expected from the main verb), or

b) together with the infinitive at the end of the sentence

► Budu tam na tebe čekat. (I’ll be waiting for you there.)

► Zítra tam na tebe budu čekat. (I’ll be waiting for you there tomorrow.)

In fact, this applies not only to the future tense, but also to modal verbs forming phrases with the infinitive (můžu čekat, musím čekat, chci čekat…):

► Můžu tam na tebe čekat. (I can wait for you there.)

► Zítra tam na tebe můžu čekat. (I can wait for you there tomorrow.)

The second-position words obediently place themselves in the expected order.

Here’s one more proof of how budu acts and how the main verb often ends up at the end of the sentence:

► Budu vám o tom vyprávět. (I’ll be telling you about it.)

► Těším se, až vám o tom budu vyprávět. (I look forward to telling you about it.)

► Těším se, až vám o tom zítra večer u večeře budu vyprávět. (I look forward to telling you about it tomorrow evening at dinner.)

More pronouns

Let’s see how we deal with the word order when there are more pronouns in the sentence. Feel free to scroll up and review the table with the hierarchy of the second-position words.

► Představím ti ji tam. (I’ll introduce her to you there.)

► Potom ti ji tam představím. (Then I’ll introduce her to you there.)

► Viděl jsem tě tady. (I saw / I’ve seen you here.)

► Už jsem tě tady viděl. (I’ve already seen you here.)

► Řekli jim to. (They told them.)

► Najednou jim to řekli. (Suddenly they told them.)

► Počkám tam na tebe. (I’ll wait for you there.)

► Asi tam na tebe počkám. (I guess I’ll wait for you there.)

Enough of me explaining. Are you up for some practice?