Making Nouns from Verbs in Czech

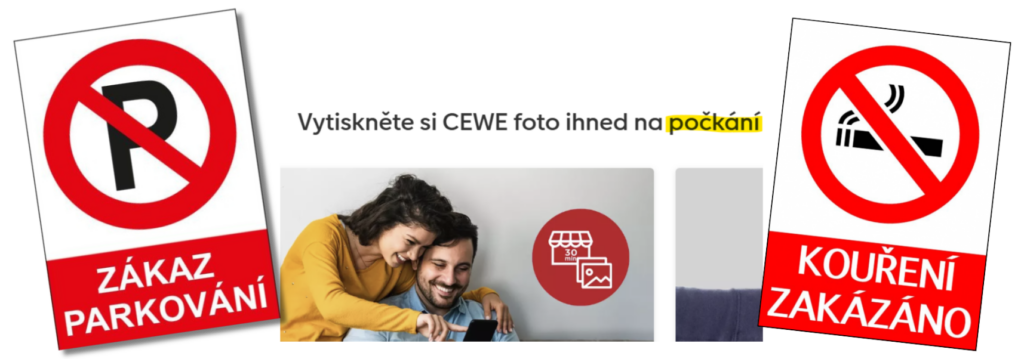

Have you noticed that there are quite a few words in Czech that end in -ání or -ení? For example, zákaz zastavení (no stopping), zákaz parkování (no parking), kouření zakázáno (smoking prohibited), mytí aut (car washing) or tisk fotografií na počkání (instant photo printing). These are the phrases you can find around you in a Czech-speaking environment.

Check out my printable worksheet, which has all the information from this article (and more) and extra exercises! You will get 10 pages and 6 exercises.

Zastavení, parkování, počkání, kouření… There is a pattern, isn’t there? These words are all nouns. To be exact, they are verbal nouns, in other words, nouns created from verbs. Zastavení came from the verb zastavit, parkování from parkovat, počkání from počkat.

If you value your time at least a bit, it’s smart to take a closer look at how these nouns are made. Once you know how, it will help you expand your vocabulary. Or at least experience one aha-moment in learning Czech. Let’s not waste time!

Here’s how you make these nouns:

Verbs that end in –at (including –ovat) will convert into nouns ending in –ání. See this example:

dělat (do, make) → dělání (doing, making)

dělat + –ání = dělání

That was easy, wasn’t it? Here’s more:

+ –ání:

hledat → hledání (searching)

počkat → počkání (waiting)

plavat → plavání (swimming)

počítat → počítání (counting)

cestovat → cestování (traveling)

pracovat → pracování (working)

fungovat → fungování (functioning)

malovat → malování (painting)

Many verbs in Czech also finish in –át. The funny thing is, the nouns from such verbs will usually take a short ending, –aní.

+ –aní:

psát → psaní (writing)

hrát → hraní (playing)

spát → spaní (sleeping)

prát → praní (washing clothes)

! stát → stání (standing) …I said usually…

What will happen with verbs ending in –it, –et or –ět? After removing the verb ending, we will then add

+ –ení:

vařit → vaření (cooking)

učit → učení (se) (learning/teaching)

řešit → řešení (solving/solution)

oznámit → oznámení (announcing/announcement)

umět → umění (skill/art)

bydlet → bydlení (living)

Watch out for certain consonants. When they’re followed by i or ě in the verb ending, it can change the ending in the derived noun so that the same sound is maintained, e.g. měnit (n is pronounced a [ň]) will have [ň] sound in the noun as well, and since we cannot say “měniní“, we change –ení to –ění to keep the same sound.

měnit → měnění (changing)

svědit → svědění (itching)

dráždit → dráždění (irritating)

So far so good? Before we move on, let’s practice with more verbs:

There are a few really short verbs, they only have one syllable. In that case, we won’t take away the verb ending. Instead, we will add –í and what we take away is the acute accent (í/ý)… So not pítí, but pití.

+ –í:

pít + í → pití (drink, drinking)

mýt → mytí (washing)

být → bytí (being)

And finally, something more interesting: verbs that end in –out. I already wrote a blog post about them in the past, feel free to check it out here. Let’s take a look at the verb rozhodnout (to decide) and convert it into a decision. In this case, we remove –out and add –utí: rozhodnutí.

+ –utí:

odmítnout → odmítnutí (refusing/refusal)

pronajmout → pronajmutí (renting)

stárnout → stárnutí (aging)

hubnout → hubnutí (losing weight)

That wasn’t so bad, was it? But wait, now we are getting into the most exciting part – the irregular changes. Certain letters change in the noun. For example, –d– before the verb ending often changes into –z–. Unbelievable, right?

–dit → –zení:

řídit → řízení (driving/management)

sedět → sezení (sitting/session)

chodit → chození (walking)

narodit se → narození (birth)

–T– doesn’t want to stay behind and joins the trend:

–tit → –cení:

platit → placení (paying)

potit → pocení (sweating)

vrátit → vrácení (returning/return)

And the nouns derived from verbs ending in –st and –ct are just all over the place!

péct → pečení (baking) (because, in the present tense, we say já peču)

jíst → jedení (eating)

vést → vedení (leading/management) (because we say já vedu)

kvést → kvetení (blooming) (já kvetu)

And now, the cherry on the cake, the verb číst.

číst → čtení (reading)

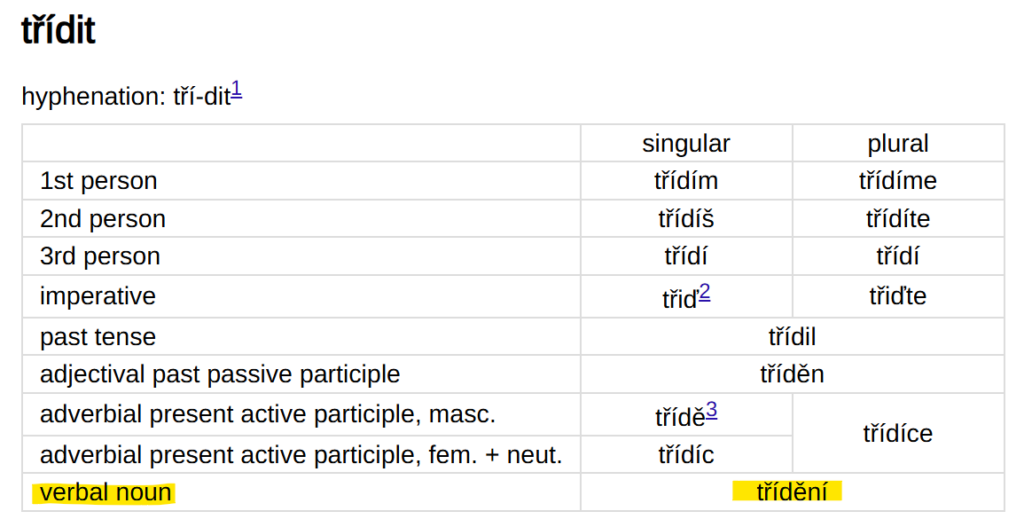

The funny thing is, you could think that since řídit turns into řízení, třídit (sort, separate) would be třízení but no… it’s třídění!

Things escalated very quickly, as you can see. So what’s the solution, how can you trust these rules? You can’t… As we say in Czech: “Důvěřuj, ale prověřuj.” “Trust, but verify.” (Maybe it was invented by a linguist.) In other words, when you find a verb you want to convert into a noun, check it in the Language Reference Book when you have the time.

Remember that while you can make nouns out of any verb, it doesn’t mean that the noun is used. For example, the verbal noun of smát se (laugh) would be smání but it’s hardly used. Instead, we use the noun smích (laughter).

And there’s one more thing I’d like to tell you. Knowing the verbal nouns also helps you correctly remember the adjectives. Look at this:

řídit → řízení (driving, noun), řízený (controlled/driven, adjective)

třídit → třídění (sorting, n.), tříděný (separation, adj.)

péct → pečení (baking, n.), pečený (baked, adj.)

Practice making nouns from these verbs (watch out, there are some irregularities):

And before you go, do this final exercise:

Here is when you can get my 10-page worksheet focused on this topic.

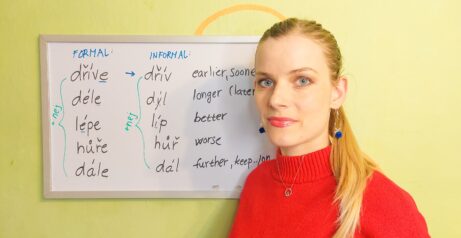

What about watching a video about this so the knowledge sticks? You only need 14 minutes!